Malawians will head to the polls on September 16 to elect a new president in an election overshadowed by economic hardship and growing public disillusionment with the country’s political class.

Seventeen candidates are in the race, including three former presidents and the sitting vice president. But despite the unusually crowded field, many voters say they see little hope for meaningful change in one of the world’s poorest nations.

“Whether it is Chakwera or (former president Peter) Mutharika, nothing changes for us. It’s like choosing between two sides of the same coin,” said Victor Shawa, a 23-year-old unemployed resident of Lilongwe.

President Lazarus Chakwera, 70, is seeking a second term after his 2020 election victory, which followed the annulment of the disputed 2019 results. Initially hailed as a reformer, his popularity has waned amid runaway inflation nearing 30 percent, chronic fuel and forex shortages, and corruption scandals involving senior officials.

“I will vote for Chakwera because he has improved road infrastructure and supported youth businesses,” said 20-year-old trader Mervis Bodole. “But the cost of living is still too high and many of us are struggling.”

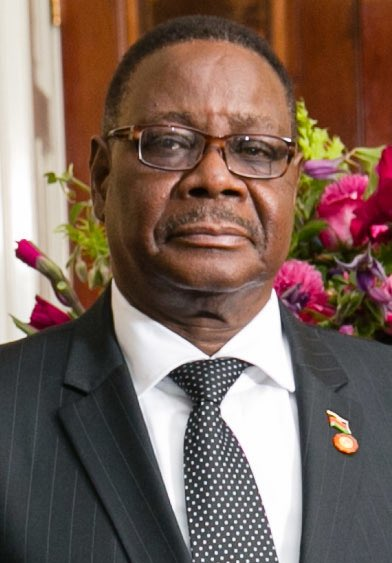

Mutharika, 85, who governed from 2014 to 2020, is banking on voter frustration to revive his fortunes, though his own tenure was marred by stagnation, shortages, and allegations of cronyism.

A recent survey by the Institute of Public Opinion and Research (IPOR) placed Mutharika in the lead with 41 percent, compared to Chakwera’s 31 percent. With victory requiring over 50 percent, analysts predict a second-round runoff is almost certain.

Other contenders include former president Joyce Banda, Vice President Michael Usi, and former central bank governor Dalitso Kabambe, who currently polls a distant third but could play a kingmaker role.

For most Malawians, the election boils down to one central issue: the economy.

“Inflation, fuel shortages, and corruption have eroded public trust in Chakwera, whose support has nearly halved since 2020,” said Boniface Dulani, a politics lecturer at the University of Malawi.

Malawi’s economy has also been battered by external shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic, Cyclone Freddy in 2023 that killed more than 1,200 people, and repeated droughts. Critics argue these events exposed the government’s lack of a coherent economic strategy.

“When people cannot afford food, when jobs are scarce, when inflation is out of control — those factors influence the vote more than anything else,” said Bertha Chikadza, president of the Economics Association of Malawi.

For younger voters, frustration runs deep. “Young people are told we are the future,” Shawa said. “But when we look at these elections, all we see are the same old faces fighting for power while we fight to survive.”