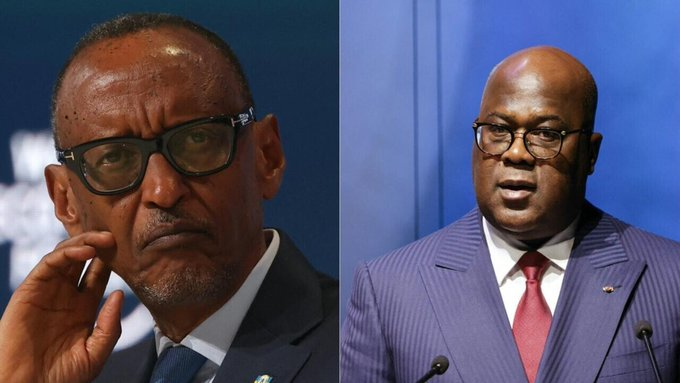

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda are poised to sign a landmark peace agreement in Washington on Friday, in a U.S.-facilitated effort to end decades of deadly conflict in eastern Congo and secure access to vital mineral resources in the region.

The deal comes as Congo continues to grapple with violent unrest driven by more than 100 armed groups, including the M23 rebel faction widely believed to be supported by Rwanda. The group’s recent offensive earlier this year led to mass killings and further displacement, adding to the 7 million people already uprooted by the conflict.

U.S. State Department deputy spokesperson Tommy Pigott said the agreement will focus on key provisions such as respect for territorial integrity, cessation of hostilities, and the disarmament and reintegration of non-state armed actors.

United Nations spokesperson Stephane Dujarric welcomed the development, emphasizing the urgency of ending the immense suffering endured by civilians, including hunger, sexual violence, and forced displacement. “This is one of the most protracted and complex humanitarian crises on Earth,” he said.

The peace agreement, hailed by former U.S. President Donald Trump as “a great day for Africa and for the world,” is part of broader regional mediation efforts involving the African Union and Qatar.

Despite the promise of the deal, doubts persist over its effectiveness. The M23 rebels, who have been accused of atrocities in eastern Congo, are not signatories to the agreement and have expressed skepticism.

Corneille Nangaa, leader of the Congo River Alliance—which includes M23—dismissed the deal, saying, “Anything regarding us that is done without us, is against us.” M23 spokesperson Oscar Balinda reiterated this stance, telling the Associated Press that the group does not consider the U.S.-brokered agreement binding.

The peace agreement also carries economic significance. Analysts say American involvement is partly motivated by strategic interests in Congo’s mineral wealth. The U.S. Department of Commerce estimates the region holds $24 trillion worth of untapped critical minerals essential to modern technology.

A separate minerals deal, currently under negotiation, could give American companies broader access to these resources, tying Washington’s commitment to Congo’s security to its economic interests.

While some view the agreement as a step toward stability, critics warn it may sideline accountability. Christian Moleka, a political analyst at the Congolese think tank Dypol, called the deal a “major turning point” but cautioned that it ignores justice for war victims.

“This seems like a trigger-happy proposition and cannot establish lasting peace without justice and reparation,” Moleka said.

In North Kivu province—one of the hardest-hit areas—activists expressed cautious optimism. Hope Muhinuka, a local peace advocate, said, “I don’t think the Americans should be trusted 100%. It is up to us to capitalize on all we have now as an opportunity.”

As Congo and Rwanda prepare to sign the agreement, many see it as a hopeful step toward ending one of Africa’s most enduring and devastating conflicts—but also one that raises questions about inclusion, justice, and the real beneficiaries of peace.