As ominous clouds loomed overhead, members of Uganda’s long-suppressed opposition—young and old—gathered for prayers at the home of an imprisoned political figure, striking a tone that was both defiant and sombre.

Kampala Mayor Erias Lukwago addressed the gathering on Sunday described the upcoming election as a direct confrontation between ordinary Ugandans and President Yoweri Museveni, who has ruled the country for nearly four decades.

“You all fall into two categories: political prisoners and potential political prisoners,” Lukwago told supporters.

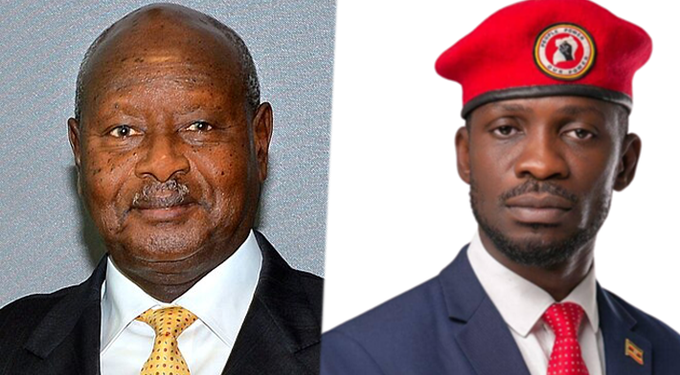

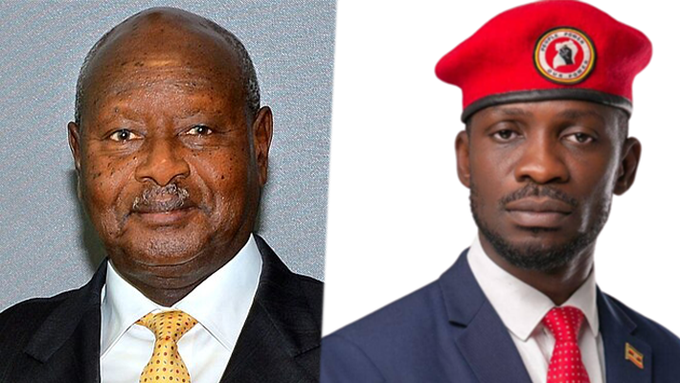

Museveni, 81, is widely expected to secure another term in Thursday’s election, buoyed by his firm grip on state institutions and the security apparatus. Having come to power as a bush fighter in the 1980s, he has maintained a heavily militarised rule, frequently cracking down on dissent.

The current campaign has been marked by widespread repression. Hundreds of opposition supporters have been arrested, and at least one person has been killed, with police insisting they are dealing with “hooligans.”

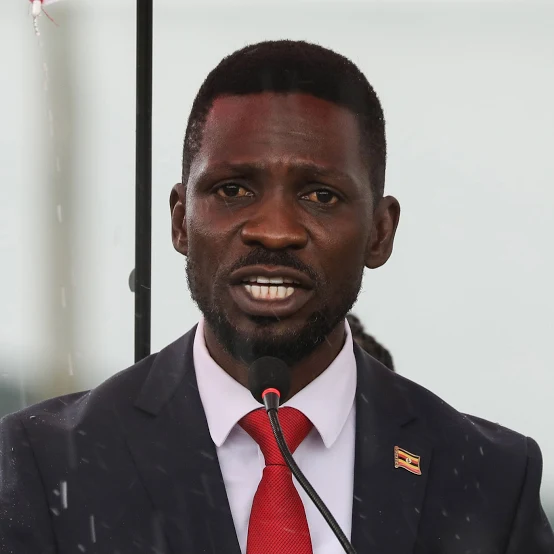

Leading opposition candidate Bobi Wine, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, now rarely appears in public without a flak jacket and has described the campaign as a “war.” He has been arrested multiple times in the past and says he was tortured while in military custody.

Uganda’s only other major opposition figure, Kizza Besigye, was abducted in Kenya in 2024 and secretly transferred to a Ugandan military detention facility, where he is facing treason charges in a case that has dragged on for months.

Sunday’s prayer session was hosted by Besigye’s wife, Winnie Byanyima, the executive director of UNAIDS. She said Uganda operates under only a “thin veneer” of democracy.

“We are really a military state,” Byanyima said. “There is total capture of state institutions by the individual who holds military power, President Museveni.”

Jude Kagoro, a researcher at the University of Bremen who has studied African policing for over a decade, said Uganda’s police force does not view itself as politically neutral.

“Most officers see it as their duty to defend the incumbent power,” Kagoro said, noting that security forces often need no direct orders to violently disperse opposition rallies.

He added that the Museveni administration has long relied on tactics to infiltrate and fragment opposition groups, including financial inducements targeted at ethnic communities. Under an informal system known as “ghetto structures,” young people in opposition strongholds are recruited to spy on activists and disrupt opposition activities.

The government was initially caught off guard by Bobi Wine’s rise ahead of the 2021 election, when he emerged as a powerful voice for urban youth. Authorities responded with widespread violence. Since then, analysts say the state has become far more prepared.

“For more than four years now, they have been building an infrastructure capable of withstanding any opposition pressure,” Kagoro said. “The presence of soldiers and police on the streets during elections has become normal.”

Despite this preparedness, authorities appear unwilling to take risks. Voters have been advised to cast their ballots and return home immediately.

“The regime wants people to be very afraid so they don’t come out to vote,” said David Lewis Rubongoya, secretary-general of the National Unity Platform, Bobi Wine’s party.

There has been a surge in arrests and abductions targeting opposition figures—a trend rights groups say is increasingly common across East Africa, including in Kenya and Tanzania, where governments are accused of coordinating repressive tactics.

The climate of fear has made political mobilisation extremely difficult.

“The cost of engaging in opposition politics has become extremely high,” said Kristof Titeca, a Uganda expert at the University of Antwerp. “What remains is a small core of committed supporters. A broad grassroots opposition no longer exists—it’s simply too dangerous.”