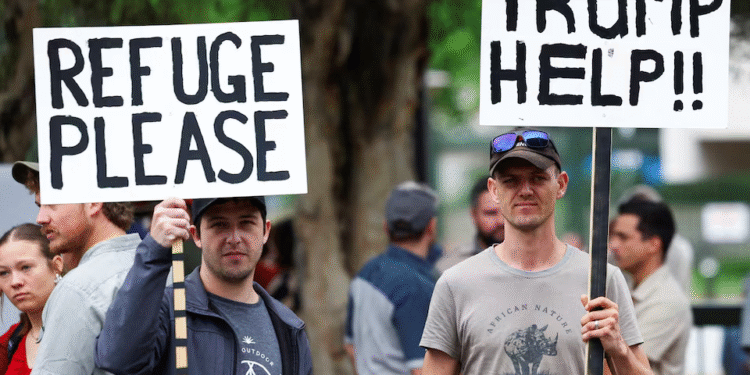

A growing number of white South Africans, particularly Afrikaners, are seeking refugee status in the United States, citing concerns over land disputes, rising crime, and what they describe as racial discrimination in post-apartheid South Africa. While refugee numbers from other regions face significant restrictions, the U.S. has reportedly granted interviews and even approvals to several South African applicants.

According to three applicants who spoke to Reuters, U.S. officials in Pretoria have conducted initial interviews, which they described as empathetic and encouraging. More than 30 individuals are believed to have already received preliminary approval, though the U.S. embassy and administration have not officially confirmed figures or commented on the process.

This development follows a February 7 executive order by former President Donald Trump, advocating for the resettlement of Afrikaner refugees in the U.S., citing their alleged persecution and “unjust racial discrimination.” This came even as Trump suspended most refugee admissions from other countries, including those facing severe conflict like Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Applicants such as Mark, a farmer injured in a 2023 attack, say they have suffered both physical harm and economic hardship due to South Africa’s Black empowerment laws. These laws aim to redress historical exclusion under apartheid but are viewed by some white citizens as discriminatory.

Despite these claims, crime data from South African police shows that the vast majority of the country’s 26,000 annual murder victims are Black. Only 44 deaths were linked to farming communities, contradicting the narrative of widespread targeted violence against white farmers. Government officials and experts have also dismissed accusations of a “white genocide” as unfounded.

“There is no evidence whatsoever that crime deliberately targets a particular race in this country,” said Chrispin Phiri, spokesperson for South Africa’s foreign affairs ministry.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials acknowledged that some applicants had received preliminary approval but emphasized that all cases would still be evaluated on an individual basis. One DHS source said there is internal skepticism among some refugee officers about the merit of these claims, noting that economic hardship alone does not meet the threshold for refugee status.

Nevertheless, interest among white South Africans has surged, with over 67,000 reportedly expressing interest in relocating to the U.S. Informal support networks and WhatsApp groups have formed, with some even discussing how to transport their pets to America.

Critics argue that this move reflects a problematic framing of white victimhood, especially given South Africa’s deep-rooted economic inequality. Afrikaners, who make up about 60% of the white minority in a nation of 63 million, still hold significant economic power. White households possess roughly 20 times more wealth than Black households, and three-quarters of private land remains under white ownership.

“The idea of white victimhood suggests that bad things happening to white people are infinitely worse than the same things happening to anybody else,” said Nicky Falkof, head of the Centre for Diversity Studies at the University of Witwatersrand.

While the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services emphasized that all relevant evidence would be considered in refugee claims, the controversy underscores the tension between race, privilege, and the meaning of persecution in global migration policies.